| Choctaw Nation Chahta Yakni |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| — Domestic dependent nation — | |||

|

|||

| Anthem: (none) ("Nahata Fichik Tohwikeli" used for some occasions) |

|||

| Established | September 27, 1830 (Treaty) | ||

| Expansions | 1843–1855 | ||

| Reductions | 1860–1867 | ||

| Constitution | January 11, 1860 | ||

| Capital | Durant, Tuskahoma | ||

| Government | |||

| • Body | Choctaw Nation Tribal Council | ||

| • Chief | Gary Batton | ||

| • Assistant Chief | Jack Austin, Jr. | ||

| Area | |||

| • Total | 28,140 km2 (10,864 sq mi) | ||

| Time zone | CST | ||

| Website | choctawnation.com/ | ||

| Total population |

|---|

| 223,279 total enrollment, 84,670 enrolled in Oklahoma[1] |

| Regions with significant populations |

| United States (Oklahoma) |

| Languages |

|

English, Choctaw |

| Religion |

|

Protestantism |

| Related ethnic groups |

|

other Choctaw tribes, Chickasaw |

The Choctaw Nation (Template:Lang-cho) (officially referred to as the Choctaw Nation of Oklahoma) is a federally recognized Native American tribe with a tribal jurisdictional area and reservation comprising 10.5 counties in Southeastern Oklahoma. The third-largest federally recognized tribe in the United States, Choctaw Nation maintains a special relationship with both the federal and Oklahoma governments. The tribe is the successor of the original Choctaw Republic which existed before Oklahoma statehood in Indian Territory. Members are sometimes referred to as Northern Choctaw.

As of 2011, the tribe has 223,279 enrolled members, of whom 84,670 live within the state of Oklahoma[2] and 41,616 live within the Choctaw Nation's jurisdiction.[3] A total of 233,126 people live within these boundaries. The tribal jurisdictional area is 10,864 square miles (28,140 km2).[4]

The chief of the Choctaw Nation is Gary Batton, who took office on April 29, 2014, after the retirement of Gregory E. Pyle.[5] The Choctaw Nation Headquarters, which houses the office of the Chief, is located in Durant.[1] Durant is also the seat of the tribe's judicial department, housed in the Choctaw Nation Judicial Center, near the Headquarters. The tribal legislature meets at the Council House, across the street from the historic Choctaw Capitol Building, in Tuskahoma. The Capitol Building has been adapted for use as the Choctaw Nation Museum. The largest city in the nation is McAlester.

The Choctaw Nation is one of three federally recognized Choctaw tribes; the others are the sizable Mississippi Band of Choctaw Indians, with 10,000 members and territory in several communities, and the Jena Band of Choctaw Indians in Louisiana, with a few hundred members. The latter two bands are descendants of Choctaw who resisted the forced relocation to Indian Territory. The Mississippi Choctaw preserved much of their culture in small communities and reorganized as a tribal government in 1945 under new laws after the Indian Reorganization Act of 1934.

Those Choctaw who removed to the Indian Territory, a process that went on into the early 20th century, are federally recognized as the Choctaw Nation of Oklahoma.[6] The removals became known as the "Trail of Tears."

Geography[]

The Choctaw Nation of Oklahoma's tribal jurisdictional area covers 10,864 square miles (28,140 km2), encompassing eight whole counties and parts of five counties in Southeastern Oklahoma:

- Atoka County,

- most of Bryan County,

- Choctaw County,

- most of Coal County,

- Haskell County,

- half of Hughes County,

- a portion of Johnston County,

- Latimer County,

- Le Flore County,

- McCurtain County,

- Pittsburg County,

- a portion of Pontotoc County, and

- Pushmataha County.

Politically, the Choctaw Nation is predominantly encompassed by Oklahoma's 2nd congressional district, represented by Republican Markwayne Mullin, a Cherokee. However some smaller strands are located within the 4th congressional district, represented by Republican Tom Cole, a Chickasaw.

Government[]

The former Choctaw Nation Headquarters in Durant

The historic Choctaw Capitol in Tuskahoma, now used as a museum of the nation

The Tribal Headquarters are located in Durant. Opened in June 2018, the new headquarters is a 5-story, 500,000 square foot building located on an 80-acre campus in south Durant. It is near other tribal buildings, such as the Regional Health Clinic, Wellness Center, Community Center, Child Development Center, and Food Distribution.[7] Previously, headquarters was located in the former Oklahoma Presbyterian College, with more offices scattered around Durant. The current chief is Gary Batton[5] and the assistant chief is Jack Austin, Jr. The Tribal Council meet monthly at Tvshka Homma.

The tribe is governed by the Choctaw Nation Constitution, which was ratified by the people on June 9, 1984. The constitution provides for an executive, a legislative and a judicial branch of government. The chief of the Choctaw Tribe, elected every four years, is not a voting member of the Tribal Council. These members are elected from single-member districts for four-year terms. The legislative authority of the tribe is vested in the Tribal Council, which consists of twelve members.

The General Fund Operating Budget, the Health Systems Operating Budget, and the Capital Projects Budget for the fiscal year beginning October 1, 2017 and ending September 30, 2018 was $516,318,568.[8]

The Choctaw Nation also has the right to appoint a non-voting delegate to the U.S. House of Representatives, per the 1830 Treaty of Dancing Rabbit Creek; as of 2019 however, no delegate has been named or sent to the Congress by the Choctaw Nation. Chief Gary Batton is said to be observing the process of the Cherokee Nation nominating their treaty-stipulated delegate to the U.S. House before proceeding.

Executive Department[]

The supreme executive power of the Choctaw Nation is assigned to a chief magistrate, styled as the "Chief of the Choctaw Nation". The Assistant Chief is appointed by the Chief with the advice and consent of the Tribal Council, and can be removed at the discretion of the Chief.[9] The current Chief of the Choctaw Nation is Gary Batton, and the current Assistant Chief is Jack Austin, Jr.

The Chief's birthday (Batton's is December 15) is a tribal holiday.

History[]

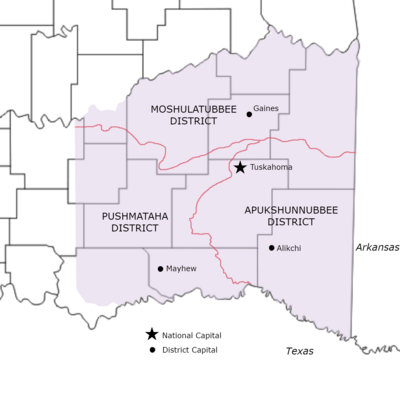

Before Oklahoma was admitted to the union as a state in 1907, the Choctaw Nation was divided into three districts: Apukshunnubbee, Moshulatubbee, and Pushmataha. Each district had its own chief from 1834 to 1857; afterward, the three districts were put under the jurisdiction of one chief. The three districts were re-established in 1860, again each with their own chief, with a fourth chief to be Principal Chief of the tribe.[10] These districts were abolished at the time of statehood, as tribal government and land claims were dissolved in order for the territory to be admitted as a state. The tribe later reorganized to re-establish its government.

List of Chiefs[]

Former districts and capitals of Choctaw Nation, Indian Territory, that existed from 1834-1857, shown with present-day Oklahoma counties.

| Choctaw Nation, Indian Territory (1834-1906) |

Districts | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Moshulatubbee | Apukshunnubbee | Pushmataha | ||||

| District [Chief bobs] | Term | District Chief | Term | District Chief | Term | |

| Moshulatubbee | 1834-1836 | Thomas LeFlore | 1834-1838 | Nitakechi | 1834-1838 | |

| Joseph Kincaid | 1836-1838 | |||||

| John McKinney | 1838-1842 | James Fletcher | 1838-1842 | Pierre Juzan | 1838-1841 | |

| Nathaniel Folsom | 1842-1846 | Thomas LeFlore | 1842-1850 | Isaac Folsom | 1841-1846 | |

| Peter Folsom | 1846-1850 | Salas Fisher | 1846-1850 | |||

| Cornelius McCurtain | 1850-1854 | George W. Harkins | 1850-1857 | George Folsom | 1850-1854 | |

| David McCoy | 1854-1857 | Nicholas Cochnauer | 1854-1857 | |||

| Districts abolished in 1857 | ||||||

| Unified Nation | ||||||

| Governor | Term | |||||

| Alfred Wade | 1857-1858 | |||||

| Tandy Walker | 1858-1859 | |||||

| Basil LeFlore | 1859-1860 | |||||

| Principal Chief | Term | |||||

| George Hudson | 1860-1862 | |||||

| Samuel Garland | 1862-1864 | |||||

| Peter Pitchlynn | 1864-1866 | |||||

| Allen Wright | 1866-1870 | |||||

| William Bryant | 1870-1874 | |||||

| Coleman Cole | 1874-1878 | |||||

| Isaac Levi Garvin | 1878-1880 | |||||

| Jackson F. McCurtain | 1880-1884 | |||||

| Edmund McCurtain | 1884-1886 | |||||

| Thompson McKinney | 1886-1888 | |||||

| Benjamin Smallwood | 1888-1890 | |||||

| Wilson N. Jones | 1890-1894 | |||||

| Jefferson Gardner | 1894-1896 | |||||

| Green McCurtain | 1896-1900 | |||||

| Gilbert Wesley Dukes | 1900-1902 | |||||

| Choctaw Nation of Oklahoma (1906–Present) | ||||||

| Chief | Term | |||||

| Green McCurtain | 1902-1910 (Appointed by Roosevelt in 1906) | |||||

| Victor Locke, Jr. | 1910-1918 (Appointed by Taft) | |||||

| William F. Semple | 1918-1922 (Appointed by Wilson) | |||||

| William H. Harrison | 1922-1929 (Appointed by Harding) | |||||

| Ben Dwight | 1929-1937 (Appointed by Hoover) | |||||

| William A. Durant | 1937-1948 (Appointed by Roosevelt) | |||||

| Harry J. W. Belvin |

1948-1959 | |||||

| C. David Gardner | 1975-1978 | |||||

| Hollis E. Roberts | 1978-1997 | |||||

| Gregory E. Pyle | 1997-2014 | |||||

| Gary Batton | 2014–Present | |||||

Legislative department[]

The legislative authority is vested in the Tribal Council. Members of the Tribal Council are elected by the Choctaw people, one for each of the twelve districts in the Choctaw Nation.[11]

Current district map of the Choctaw Nation of Oklahoma.

| Current Tribal Council | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| District | Portrait | Councilman | First elected | Term ends |

| District 1 | Thomas Williston | November 29, 2010 | September 4, 2023 | |

| District 2 | Johnathan Ward | September 7, 2015 | September 4, 2023 | |

| District 3 | Eddie Bohanan | September 2, 2019 | September 4, 2023 | |

| District 4 | Delton Cox | September 3, 2001 | September 5, 2021 | |

| District 5 | Ronald Perry | September 5, 2011 | September 4, 2023 | |

| District 6 | Jennifer Woods | September 4, 2017 | September 5, 2021 | |

| District 7 | Jack Austin | September 3, 2001 | September 5, 2021 | |

| District 8 | Perry Thompson | September 1, 1987 | September 4, 2023 | |

| District 9 | James Dry | September 4, 2017 | September 5, 2021 | |

| District 10 | Anthony Dillard | September 5, 2005 | September 5, 2021 | |

| District 11 | Robert Karr | September 2, 2019 | September 4, 2023 | |

| District 12 | James Frazier | September 3, 1990 | September 5, 2021 | |

Award-winning painter Norma Howard is enrolled in the Choctaw Nation of Oklahoma.

In order to be elected as council members, candidates must have resided in their respective districts for at least one year immediately preceding the election. "Candidates for the Tribal Council must be at least one-fourth (1/4) Choctaw Indian by blood and must be twenty-one (21) years of age or older at the time they file for election."[12] Once elected, a council member must remain a resident of the district from which he or she was elected during the term in office. This policy ensures the involvement and interaction of successful candidates with their constituency.

Once in office, the Tribal Council members have regularly scheduled county council meetings. The presence of these tribal leaders in the Indian community creates a sense of understanding of their community and its needs. The Tribal Council is responsible for adopting rules and regulations which govern the Choctaw Nation, for approving all budgets, making decisions concerning the management of tribal property, and all other legislative matters. The Tribal Council Members are the voice and representation of the Choctaw people in the tribal government.

The Tribal Council assists the community to implement an economic development strategy and to plan, organize, and direct Tribal resources to achieve self-sufficiency. The Tribal Council is working to strengthen the Nation's economy, with efforts being focused on the creation of additional job opportunities through promotion and development. By planning and implementing its own programs and building a strong economic base, the Choctaw Nation applies its own fiscal, natural, and human resources to develop self-sufficiency.

Judicial department[]

The judicial authority of the Choctaw Nation is assigned to the Court of General Jurisdiction (which includes the District Court and the Appellate Division) and the Constitutional Court. The Constitutional Court consists of a three-member court, who are appointed by the Chief. At least one member, the presiding judge (Chief Justice), must be a lawyer licensed to practice before the Supreme Court of Oklahoma.

Members[]

- Constitutional Court[13]

–Chief Justice David Burrage

–Judge Mitch Mullen

–Judge Frederick Bobb

- Appellate Division[14]

–Presiding Judge Pat Phelps

–Judge Bob Rabon

–Judge Warren Gotcher

- District Court[15]

–Presiding District Judge Richard Branam

–District Judge Mark Morrison

–District Judge Rebecca Cryer

Economy[]

The Choctaw Nation's annual tribal economic impact in 2010 was over $822,280,105.[16] The tribe employs nearly 8,500 people worldwide;[17] 2,000 of those work in Bryan County, Oklahoma. The Choctaw Nation is also the largest single employer in Durant. The nation's payroll is about $260 million per year, with total revenues from tribal businesses and governmental entities topping $1 billion.

The nation has contributed to raising Bryan County's per capita income to about $24,000. The Choctaw Nation has helped build water systems and towers, roads and other infrastructure, and has contributed to additional fire stations, EMS units and law enforcement needs that have accompanied economic growth.

The Choctaw Nation operates several types of businesses. It has seven casinos, 14 tribal smoke shops, 13 truck stops, and two Chili's franchises in Atoka and Poteau.[1] It also owns a printing operation, a corporate drug testing service, hospice care, a metal fabrication and manufacturing business, a document backup and archiving business, and a management services company that provides staffing at military bases, embassies and other sites, among other enterprises.

Health system[]

Choctaw Nation Tribal Services Center in Hugo, Oklahoma

The Choctaw Nation is the first indigenous tribe in the United States to build its own hospital with its own funding.[18] The Choctaw Nation Health Care Center, located in Talihina, is a 145,000-square-foot (13,500 m2) health facility with 37 hospital beds for inpatient care and 52 exam rooms. The $22 million hospital is complete with $6 million worth of state-of-the-art equipment and furnishing. It serves 150,000–210,000 outpatient visits annually. The hospital also houses the Choctaw Nation Health Services Authority, the hub of the tribal health care services of Southeastern Oklahoma.

The tribe also operates eight Indian clinics, one each in Atoka, Broken Bow, Durant, Hugo, Idabel, McAlester, Poteau, and Stigler.

2008 Freedom Award[]

In July 2008, the United States Department of Defense announced the 2008 Secretary of Defense Employer Support Freedom Award recipients. They are awarded the highest recognition given by the U.S. Government to employers for their outstanding support of employees who serve in the National Guard and Reserve.

The Choctaw Nation was one of 15 recipients of that year's Freedom Award, selected from 2,199 nominations. Its representatives received the award September 18, 2008 in Washington, D.C. The Choctaw Nation is the first Native American tribe to receive this award.

History[]

Treaty of Dancing Rabbit Creek (1830)[]

At Andrew Jackson's request, the United States Congress opened a fierce debate on an Indian Removal Bill.[19] In the end, the bill passed, but the vote was very close: The Senate passed the measure, 28 to 19, while in the House it passed, 102 to 97. Jackson signed the legislation into law June 30, 1830,[19] and turned his focus onto the Choctaw in Mississippi Territory.

On August 25, 1830, the Choctaws were supposed to meet with Jackson in Franklin, Tennessee, but Greenwood Leflore, a district Choctaw chief, informed Secretary of War John H. Eaton that the warriors were fiercely opposed to attending.[20] Jackson was angered. Journalist Len Green writes "although angered by the Choctaw refusal to meet him in Tennessee, Jackson felt from LeFlore's words that he might have a foot in the door and dispatched Secretary of War Eaton and John Coffee to meet with the Choctaws in their nation."[21] Jackson appointed Eaton and General John Coffee as commissioners to represent him to meet the Choctaws at the Dancing Rabbit Creek near present-day Noxubee County, Mississippi.

Say to them as friends and brothers to listen [to] the voice of their father, & friend. Where [they] now are, they and my white children are too near each other to live in harmony & peace.... It is their white brothers and my wishes for them to remove beyond the Mississippi, it [contains] the [best] advice to both the Choctaws and Chickasaws, whose happiness... will certainly be promoted by removing.... There... their children can live upon [it as] long as grass grows or water runs.... It shall be theirs forever... and all who wish to remain as citizens [shall have] reservations laid out to cover [their improv]ements; and the justice due [from a] father to his red children will [be awarded to] them. [Again I] beg you, tell them to listen. [The plan proposed] is the only one by which [they can be] perpetuated as a nation.... I am very respectfully your friend, & the friend of my Choctaw and Chickasaw brethren. Andrew Jackson. -Andrew Jackson to the Choctaw & Chickasaw Nations, 1829.[22]

The commissioners met with the chiefs and headmen on September 15, 1830, at Dancing Rabbit Creek.[23] In carnival-like atmosphere, the policy of removal was explained to an audience of 6,000 men, women, and children.[23] The Choctaws would now face migration or submit to US law as citizens.[23] The treaty would sign away the remaining traditional homeland to the US; however, a provision in the treaty made removal more acceptable:

In 1830 Mosholatubbee sought to be elected to the Congress of the United States. 1834, Smithsonian American Art Museum

ART. XIV. Each Choctaw head of a family being desirous to remain and become a citizen of the States, shall be permitted to do so, by signifying his intention to the Agent within six months from the ratification of this Treaty, and he or she shall thereupon be entitled to a reservation of one section of six hundred and forty acres of land.... -Treaty of Dancing Rabbit Creek, 1830

On September 27, 1830, the Treaty of Dancing Rabbit Creek was signed. It represented one of the largest transfers of land that was signed between the US government and Native Americans without being instigated by warfare. By the treaty, the Choctaws signed away their remaining traditional homelands, opening them up for European-American settlement. The Choctaw were the first to walk the Trail of Tears. Article XIV allowed for nearly 1300 Choctaws to remain in the state of Mississippi and to become the first major non-European ethnic group to become US citizens.[24][25][26][27] Article 22 sought to put a Choctaw representative in the U.S. House of Representatives.[24] The Choctaw at this crucial time split into two distinct groups: the Choctaw Nation of Oklahoma and the Mississippi Band of Choctaw Indians. The nation retained its autonomy, but the tribe in Mississippi submitted to state and federal laws.[28]

To the voters of Mississippi. Fellow Citizens:-I have fought for you, I have been by your own act, made a citizen of your state; ... According to your laws I am an American citizen, ... I have always battled on the side of this republic ... I have been told by my white brethren, that the pen of history is impartial, and that in after years, our forlorn kindred will have justice and "mercy too" ... I wish you would elect me a member to the next Congress of the [United] States.-Mushulatubba, Christian Mirror and N.H. Observer, July 1830.[29]

Great Irish Famine aid (1847)[]

Choctaw Stickball Player, Painted by George Catlin, 1834

Midway through the Great Irish Famine (1845–1849), a group of Choctaw collected $170 ($4,000 in current dollar terms) and sent it to help starving Irish men, women and children. "It had been just 16 years since the Choctaw people had experienced the Trail of Tears, and they had faced starvation… It was an amazing gesture. By today's standards, it might be a million dollars," wrote Judy Allen in 1992, editor of the Choctaw Nation of Oklahoma's newspaper, Bishinik. To mark the 150th anniversary, eight Irish people came to the US to retrace the Trail of Tears to raise money for Somalian relief.[30](Following publication of Angie Debo's The Rise and Fall of the Choctaw Republic, various articles corrected the cited amount of this donation, saying it was $170 ($4,000).)

In 2015 a sculpture known as Kindred Spirits was erected in the town of Midleton, County Cork, Ireland to commemorate the Choctaw Nation's donation. A delegation of 20 members of the Choctaw Nation attended the opening ceremony along with the County Mayor of Cork.

American Civil War in Indian Territory (1860-65)[]

See:Choctaw in the American Civil War

Territory transition to statehood (1900)[]

By the early twentieth century, the United States government had passed laws that reduced the Choctaw's sovereignty and tribal rights in preparation for the extinguishing of land claims and for Indian Territory to be admitted, along with Oklahoma Territory, as part of the State of Oklahoma.

Under the Dawes Act, in violation of earlier treaties, the Dawes Commission registered tribal members in official rolls. It forced individual land allotments upon the Tribe's heads of household, and the government classified land beyond these allotments as "surplus", and available to be sold to both native and non-natives. It was primarily intended for European-American (white) settlement and development.

The government created "guardianship" by third parties who controlled allotments while the owners were underage. During the oil boom of the early 20th century, the guardianships became very lucrative; there was widespread abuse and financial exploitation of Choctaw individuals. Charles Haskell, the future governor of Oklahoma, was among the white elite who took advantage of the situation.[31]

An Act of 1906 spelled out the final tribal dissolution agreements for all of the five civilized tribes and dissolved the Choctaw government. The Act also set aside a timber reserve, which might be sold at a later time; it specifically excluded coal and asphalt lands from allotment. After Oklahoma was admitted as a state in 1907, tribal chiefs of the Choctaw and other nations were appointed by the Secretary of the Interior.[32]

Pioneering the use of code talking (1918)[]

During World War I the American army fighting in France became stymied by the Germans' ability to intercept its communications. The Germans successfully decrypted the codes, and were able to read the Americans' secrets and know their every move in advance.[33]

Several Choctaw serving in the 142nd Infantry suggested using their native tongue, the Choctaw language, to transmit army secrets. The Germans were unable to penetrate their language. This change enabled the Americans to protect their actions and almost immediately contributed to a turn-around on the Meuse-Argonne front. Captured German officers said they were baffled by the Choctaw words, which they were completely unable to translate. According to historian Joseph Greenspan, the Choctaw language did not have words for many military ideas, so the code-talkers had to invent other terms from their language. Examples are "'big gun' for artillery, 'little gun shoot fast' for machine gun, 'stone' for grenade and 'scalps' for casualties."[33] Historians credit these soldiers with helping bring World War I to a faster conclusion.

There were fourteen Choctaw Code Talkers. The Army repeated the use of Native Americans as code talkers during World War II, working with soldiers from a variety of American Indian tribes, including the Navajo. Collectively the Native Americans who performed such functions are known as code talkers.

Citizenship (1920s)[]

The Burke Act of 1906 provided that tribal members would become full United States citizens within 25 years, if not before. In 1928 tribal leaders organized a convention of Choctaw and Chickasaw tribe members from throughout Oklahoma. They met in Ardmore to discuss the burdens being placed upon the tribes due to passage and implementation of the Indian Citizenship Act and the Burke Act. Since their tribal governments had been abolished, the tribes were concerned about the inability to secure funds that were due them for leasing their coal and asphalt lands, in order to provide for their tribe members. Czarina Conlan was selected as chair of the convention. They appointed a committee composed of Henry J. Bond, Conlan, Peter J. Hudson, T.W. Hunter and Dr. E. N Wright, for the Choctaw; and Ruford Bond, Franklin Bourland, George W. Burris, Walter Colbert and Estelle Ward, for the Chickasaw to determine how to address their concerns.[34]

After meeting to prepare the recommendation, the committee broke with precedent when it sent Czarina Conlan (Choctaw) and Estelle Chisholm Ward (Chickasaw) to Washington, D.C. to argue in favor of passage of a bill proposed by U.S. House Representative Wilburn Cartwright. It proposed sale of the coal and asphalt holdings, but continuing restrictions against sales of Indian lands. This was the first time that women had been sent to Washington as representatives of their tribes.[35]

Termination efforts in the 1950s[]

From the late 1940s through the 1960s, the federal government considered an Indian termination policy, to end the special relationship of tribes. Retreating from the emphasis of self-government of Indian tribes, Congress passed a series of laws to enable the government to end its trust relationships with native tribes. On 13 August 1946, it passed the Indian Claims Commission Act of 1946, Pub. L. No. 79-726, ch. 959. Its purpose was to settle for all time any outstanding grievances or claims the tribes might have against the U.S. for treaty breaches (which were numerous), unauthorized taking of land, dishonorable or unfair dealings, or inadequate compensation on land purchases or annuity payments. Claims had to be filed within a five-year period.

Most of the 370 complaints submitted were filed at the approach of the 5-year deadline in August 1951.[36]

In 1946, the government had appropriated funds for the sale of Choctaw tribal coal and asphalt resources. Though the Choctaw won their case, they were charged by the courts with almost 10% of the $8.5 million award in administrative fees. In 1951, the tribe took advantage of the new law and filed a claim for over $750,000 to recover those fees.[37]

When Harry J. W. Belvin was appointed chief of the Choctaw in 1948 by the Secretary of the Interior, he realized that only federally recognized tribes were allowed to file a claim with the Commission. If he wanted to get that money back, his tribe needed to reorganize and re-establish its government. He created a democratically elected tribal council and a constitution to re-establish a government, but his efforts were opposed by the Area Director of the Bureau of Indian Affairs.

Ultimately, the Choctaw filed a claim with the Claims Commission on a technicality in 1951. The suit was classified as a renewal of the 1944 case against the US Court of Claims, but that did not stop the antagonism between Belvin and the area BIA officials.[32] The BIA had had management issues for decades. Poorly trained personnel, inefficiency, corruption, and lack of consistent policy plagued the organization almost from its founding.[38] For Belvin, relief from BIA oversight of policies and funds seemed as if it might enable the Choctaw to maintain their own traditional ways of operating and to reform their own governing council.[32]

After eleven years as Choctaw chief, Belvin persuaded Representative Carl Albert of Oklahoma to introduce federal legislation to begin terminating the Choctaw tribe.[32] On 23 April 1959, the BIA confirmed that H.R. 2722 had been submitted to Congress at the request of the tribe. It would provide for the government to sell all remaining tribal assets, but would not affect any individual Choctaw earnings. It also provided for the tribe to retain half of all mineral rights, to be managed by a tribal corporation.[39]

On 25 August 1959, Congress passed a bill[40] to terminate the tribe; it was called "Belvin's law" because he was the main advocate behind it. Belvin created overwhelming support for termination among tribespeople through his promotion of the bill, describing the process and expected outcomes. Tribal members later interviewed said that Belvin never used the word "termination" for what he was describing, and many people were unaware he was proposing termination.[41] The provisions of the bill were intended to be a final disposition of all trust obligations and a final "dissolution of the tribal governments."[39]

The original act was to have expired in 1962, but was amended twice to allow more time to sell the tribal assets. As time wore on, Belvin realized that the bill severed the tribe members' access to government loans and other services, including the tribal tax exemption. By 1967, he had asked Oklahoma Congressman Ed Edmondson to try to repeal the termination act.[32] Public sentiment was changing as well. The Choctaw people had seen what termination could do to tribes, since they witnessed the process with four other tribes in Oklahoma: the Wyandotte Nation, Peoria Tribe of Indians of Oklahoma, Ottawa Tribe of Oklahoma, and Modoc Tribe of Oklahoma. In 1969, ten years after passage of the Choctaw termination bill and one year before the Choctaws were to be terminated, word spread throughout the tribe that Belvin's law was a termination bill. Outrage over the bill generated a feeling of betrayal, and tribal activists formed resistance groups opposing termination. Groups such as the Choctaw Youth Movement in the late 1960s fought politically against the termination law. They helped create a new sense of tribal pride, especially among younger generations. Their protest delayed termination; Congress repealed the law on 24 August 1970.[41]

Self-determination 1970s-present[]

The 1970s were a crucial and defining decade for the Choctaw. To a large degree, the Choctaw repudiated the more extreme Indian activism. They sought a local grassroots solution to reclaim their cultural identity and sovereignty as a nation.

Republican President Richard Nixon ended the government's push for termination. On August 24, 1970, he signed a bill repealing the Termination Act of 1959, before the Choctaw would have been terminated. Some Oklahoma Choctaw organized a grassroots movement to change the direction of the tribal government. In 1971, the Choctaw held their first popular election of a chief since Oklahoma entered the Union in 1907.

A group calling themselves the Oklahoma City Council of Choctaws endorsed thirty-one-year-old David Gardner for chief, in opposition to the current chief, seventy-year-old Harry Belvin. Gardner campaigned on a platform of greater financial accountability, increased educational benefits, the creation of a tribal newspaper, and increased economic opportunities for the Choctaw people. Amid charges of fraud and rule changes concerning age, Gardner was declared ineligible to run. He did not meet the new minimum age requirement of thirty-five. Belvin was re-elected to a four-year term as chief.

In 1975, thirty-five-year-old David Gardner defeated Belvin to become the Choctaw Nation's second popularly elected chief. 1975 also marked the year that the United States Congress passed the landmark Indian Self-Determination and Education Assistance Act, which had been supported by Nixon before he resigned his office due to the Watergate scandal. This law revolutionized the relationship between Indian Nations and the federal government by providing for nations to make contracts with the BIA, in order to gain control over general administration of funds destined for them.

Native American tribes such as the Choctaw were granted the power to negotiate and contract directly for services, as well as to determine what services were in the best interest of their people. During Gardner's term as chief, a tribal newspaper, Hello Choctaw, was established. In addition, the Choctaw directed their activism at regaining rights to land and other resources. With the Creek and Cherokee nations, the Choctaw successfully sued the federal and state government over riverbed rights to the Arkansas River.

Discussions began on the issue of drafting and adopting a new constitution for the Choctaw people. A movement began to increase official enrollment of members, increase voter participation, and preserve the Choctaw language. In early 1978, David Gardner died of cancer at the age of thirty-seven. Hollis Roberts was elected chief in a special election, serving from 1978 to 1997.

In June 1978 the Bishinik replaced Hello Choctaw as the tribal newspaper. Spirited debates over a proposed constitution divided the people. In May 1979, they adopted a new constitution for the Choctaw nation.

Faced with termination as a sovereign nation in 1970, the Choctaws emerged a decade later as a tribal government with a constitution, a popularly elected chief, a newspaper, and the prospects of an emerging economy and infrastructure that would serve as the basis for further empowerment and growth.

Notable tribal members[]

Lane Adams (Choctaw)

Marcus Amerman (Choctaw), bead, glass, and performance artist

- Lane Adams (b. 1989), Major League Baseball player, Philadelphia Phillies (nephew of Choctaw member and attorney Kalyn Free)

- Marcus Amerman (b. 1959), bead, glass, and performance artist

- Gary Batton, (b. 1966), Chief of the Choctaw Nation

- Michael Burrage (b. 1950), former U.S. District Judge

- Sean Burrage (b. 1968), President of Southeastern Oklahoma State University

- Steve Burrage (b. 1952), former Oklahoma State Auditor and Inspector

- Choctaw Code Talkers, World War I veterans who provided a secure means of communication in their language

- Clarence Carnes (1927–1988), imprisoned at Alcatraz

- Tonya Crews (1938-1966), Playboy Playmate model Centerfold for March 1961

- Czarina Conlan (1871-1958), first woman to represent the Choctaw in Washington, D.C. and first woman elected to a school board in Oklahoma

- Samantha Crain (b. 1986), singer-songwriter, musician

- Tobias William Frazier, Sr. (1892–1975), Choctaw code talker

- Te Ata Fisher, (1895-1995), (Mary Francis Thompson Fisher), 1/4 Choctaw, Chickasaw.

- Kalyn Free, attorney

- Rosella Hightower (1920–2008), prima ballerina

- Norma Howard, visual artist

- LeAnne Howe, writer and academic

- Phil Lucas (1942–2007), filmmaker

- Green McCurtain (d. 1910), Chief from 1902–1910; appointed by US government 1906-1910

- Cal McLish (1925–2010), Major League Baseball pitcher

- Devon A. Mihesuah (b. 1957), author, editor, historian

- Joseph Oklahombi (1895-1960), Choctaw code talker

- Peter Pitchlynn (1806–1881), Chief from 1860–1866

- Gregory E. Pyle (1949-2019), former Chief of the Choctaw Nation

- Hollis E. Roberts (1943-2011), former Chief of the Choctaw Nation

- Summer Wesley, attorney, writer, and activist

- Wallis Willis, composer and Choctaw Freedman

- James Winchester (b. 1989), National Football League player

See also[]

- John Hope Franklin, African-American historian whose mother was of partial Choctaw descent

- Choctaw culture

- Choctaw mythology

- Choctaw Trail of Tears

- Jena Band of Choctaw Indians, Louisiana

- Mississippi Band of Choctaw Indians

Notes[]

- ^ a b c "2011 Oklahoma Indian Nations Pocket Pictorial Directory". Oklahoma Indian Affairs Commission. September 2011. http://www.ok.gov/oiac/documents/2011.FINAL.WEB.pdf.

- ^ https://web.archive.org/web/20120512040555/http://www.ok.gov/oiac/documents/2011.FINAL.WEB.pdf

- ^ http://www.odot.org/OK-GOV-DOCS/PROGRAMS-AND-PROJECTS/GRANTS/FASTLANE-US69/Reports-Tech-Info/Tribal%20Data.pdf

- ^ Of The Interior, United States. Dept (1916). "Annual Report of the Secretary of the Interior for the Fiscal Year". https://books.google.com/?id=B0YZAAAAYAAJ&pg=PA59&lpg=PA59&dq=cherokee+nation+total+area#v=onepage&q=cherokee%20nation%20total%20area&f=false.

- ^ a b "Executive Branch - Choctaw Nation". ChoctawNation.com. http://choctawnation.com/government/executive-branch.

- ^ Ferguson, Bob; Leigh Marshall (1997). "Chronology". Mississippi Band of Choctaw Indians. Archived from the original on 2007-10-10. https://web.archive.org/web/20071010062645/http://www.choctaw.org/history/chronology.htm.

- ^ "Choctaw Nation Opens New Headquarters | Choctaw Nation". https://www.choctawnation.com/news-events/press-media/choctaw-nation-opens-new-headquarters.

- ^ https://www.choctawnation.com/sites/default/files/import/CB-139-17.pdf

- ^ "Archived copy". https://www.choctawnation.com/sites/default/files/constitution_1983_original.pdf.

- ^ "CONTENTdm". http://digital.library.okstate.edu/Chronicles/v017/v017p192.html.

- ^ "Tribal Council Members - Choctaw Nation". choctawnation.com. Archived from the original on 2012-01-03. https://web.archive.org/web/20120103090603/http://www.choctawnation.com/government/tribal-council-members.

- ^ "Constitution of Choctaw Nation 1983". Choctaw Nation of Oklahoma. Archived from the original on 2013-12-14. https://web.archive.org/web/20131214101521/http://www.choctawnation.com/history/choctaw-nation-history/1972-1990/constitution-of-choctaw-nation-1983/.

- ^ https://www.choctawnationcourt.com/courts/constitutional-court/

- ^ https://www.choctawnationcourt.com/courts/court-of-appeals/

- ^ https://www.choctawnationcourt.com/courts/district-court/

- ^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2010-04-06. https://web.archive.org/web/20100406044653/http://www.ok.gov/oiac/Publications/.

- ^ "Great Companies Spotlight: Sovereign Nations | Oklahoma Magazine". http://www.okmag.com/blog/2012/11/26/great_companies_spotlight_sovereign_nations-2/.

- ^ "Choctawnationhealth.com". Archived from the original on September 6, 2015. https://web.archive.org/web/20150906140720/http://www.choctawnationhealth.com/1choctaw-nation-health-care-center.aspx.

- ^ a b Sharyn Kane & Richard Keeton. "As Long as Grass Grows". Fort Benning - The Land and the People. SEAC. http://www.nps.gov/history/seac/benning-book/ch11.htm.

- ^ Remini, Robert. "Brothers, Listen ... You Must Submit". Andrew Jackson. History Book Club. p. 272. ISBN 0-9650631-0-7.

- ^ Green, Len (October 1978). "Choctaw Treaties". Bishinik. Archived from the original on 2007-12-15. https://web.archive.org/web/20071215033006/http://www.tc.umn.edu/~mboucher/mikebouchweb/choctaw/chotreat.htm.

- ^ Len Green (2009). "President Andrew Jackson's Original Instructions to the "Civilized" Indian Tribes to Move West". The Raab Collection. http://www.raabcollection.com/manuscript/Andrew-Jackson-Autograph-Trail.aspx. Retrieved 2009-09-28.

- ^ a b c Remini, Robert. "Brothers, Listen ... You Must Submit". Andrew Jackson. History Book Club. ISBN 0-9650631-0-7.

- ^ a b Kappler, Charles (1904). "INDIAN AFFAIRS: LAWS AND TREATIES Vol. II, Treaties". Government Printing Office. http://digital.library.okstate.edu/kappler/Vol2/treaties/cho0310.htm. Retrieved 2008-04-16.

- ^ Baird, David (1973). "The Choctaws Meet the Americans, 1783 to 1843". The Choctaw People. United States: Indian Tribal Series. p. 36.

- ^ Council of Indian Nations (2005). "History & Culture, Citizenship Act - 1924". Council of Indian Nations. http://www.nrcprograms.org/site/PageServer?pagename=cin_hist_citizenshipact. Retrieved 2008-05-02.

- ^ Carleton, Ken (2002). "A Brief History of the Mississippi Band of Choctaw Indians". Mississippi Archaeological Association. http://www.msarchaeology.org/maa/carleton.pdf. Retrieved 2009-05-04.

- ^ Kidwell (2007); Kidwell (1995)

- ^ "An Indian Candidate for Congress". Christian Mirror and N.H. Observer, Shirley, Hyde & Co.. July 15, 1830.

- ^ Ward, Mike (1992). "Irish Repay Choctaw Famine Gift: March Traces Trail of Tears in Trek for Somalian Relief". American-Stateman Capitol. Archived from the original on 2007-10-25. https://web.archive.org/web/20071025025556/http://www.uwm.edu/~michael/choctaw/retrace.html.

- ^ Angie Debo, And Still the Waters Run, Princeton University Press, 1972, pg 159-180

- ^ a b c d e "The Resurgence of the Choctaws in the Twentieth Century". Indigenous Nations Studies Journal . 3, No. 1 (Spring 2002): 8–10.

- ^ a b "World War I’s Native American Code Talkers Greenspan, Joseph. "World War I’s Native American Code Talkers.", History, 29 May 2014. Retrieved August 19, 2014.

- ^ "Chickasaws and Choctaws to Send Delegation to Capital". The Daily Ardmoreite (Ardmore, Oklahoma): p. 3. March 25, 1928. https://newspaperarchive.com/profile/susun-wilkinson/clipnumber/66010/. Retrieved 8 August 2016.

- ^ "Indians Break Precedents to Send Women Representatives". The Daily Ardmoreite (Ardmore, Oklahoma): p. 2. April 3, 1928. https://newspaperarchive.com/profile/susun-wilkinson/clipnumber/66011/. Retrieved 8 August 2016.

- ^ Philp, Kenneth R. (1999). Termination revisited : American Indians on the trail to self-determination, 1933-1953. Lincoln [u.a.]: Univ. of Nebraska Press. pp. 21–33. ISBN 978-0-8032-3723-0. https://books.google.com/books?id=68ggiC4QtRkC&lpg. Retrieved 29 December 2014.

- ^ Kidwell (2002), pp. 10–12

- ^ "Indian Lands, Indian Subsidies". Downsizing the Federal Government. February 2012. http://www.downsizinggovernment.org/interior/indian-lands-indian-subsidies.

- ^ a b "Department Supports Choctaw Termination Bill Introduced in Congress at the Request of Tribal Representatives". Department of the Interior. http://www.bia.gov/cs/groups/public/documents/text/idc016731.pdf.

- ^ "Public Law 86-192". US Code. Archived from the original on 23 January 2012. https://web.archive.org/web/20120123135051/http://digital.library.okstate.edu/kappler/vol6/html_files/v6p0882.html.

- ^ a b (2007) "Political Protest, Conflict, and Tribal Nationalism: The Oklahoma Choctaws and the Termination Crisis of 1959–1970". American Indian Quarterly 31, No. 2 (Spring 2007): 283–309. DOI:10.1353/aiq.2007.0024.

External links[]

- Choctaw Nation of Oklahoma, official website

- Choctaw Nation Health Services Authority

- D. L. Birchfield, "Choctaws." Accessed May 15, 2015.

| |||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||