| Christianity by Country |

|---|

|

Africa

Asia

Middle East

* Lacks its own page • Full list • |

Christianity is the most adhered to religion in the United States, with 75% of polled American adults identifying themselves as Christian in 2015.[1][2] This is down from 85% in 1990, lower than 81.6% in 2001,[3] and slightly lower than 78% in 2012.[4] About 62% of those polled claim to be members of a church congregation.[5] The United States has the largest Christian population in the world, with nearly 240 million Christians, although other countries have higher percentages of Christians among their populations.

All Protestant denominations accounted for 51.3%, while the Catholic Church by itself, at 23.9%, was the largest individual denomination. A 2008 Pew study categorizes white evangelical Protestants, 26.3% of the population, as the country's largest religious cohort;[6] another study in 2004 estimates evangelical Protestants of all races at 30–35%.[7] The nation's second-largest church and the single largest Protestant denomination is the Southern Baptist Convention.[8] The United Methodist Church is the third largest church and the largest mainline Protestant denomination in the United States.[9] The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (Mormons) is the fourth-largest church in the United States and the largest church originating in the U.S.[10][11] The Church of God in Christ is the fifth-largest denomination, the largest Pentecostal church, and the largest traditionally African-American denomination in the nation.[8] Among Eastern Christian denominations, there are several Eastern Orthodox and Oriental Orthodox churches, with just below 1 million adherents in the US, or 0.4% of the total population.[12]

Christianity was introduced to the Americas as it was first colonized by Europeans beginning in the 16th and 17th centuries. Going forward from its foundation, the United States has been called a Protestant nation by a variety of sources.[13][14][15][16] Immigration further increased Christian numbers. Today most Christian churches in the United States are either Mainline Protestant, Evangelical Protestant, or Catholic.[17]

Major denominational families[]

| Christian denominations in the United States |

|---|

|

American interchurch

|

|

Anabaptist and Friends

|

|

Anglican

|

African-American Baptist

|

|

Catholic

|

|

Eastern Christian

Eastern Orthodox

Oriental Orthodox

|

|

Holiness and Pietist

|

|

|

Oneness Pentecostal

|

|

Presbyterian and Reformed

|

|

Stone-Campbell

|

|

Other

|

Christian denominations in the United States are usually divided into three large groups: Evangelical Protestantism, Mainline Protestantism, and the Catholic Church. There are also Christian denominations that do not fall within either of these groups, such as Eastern Orthodoxy and Oriental Orthodoxy, but they are much smaller.

A 2004 survey of the United States identified the percentages of these groups as 26.3% (Evangelical), 22% (Catholics), and 16% (Mainline Protestant).[7] In a Statistical Abstract of the United States, based on a 2001 study of the self-described religious identification of the adult population, the percentages for these same groups are 28.6% (Evangelical), 24.5% (Catholics), and 13.9% (Mainline Protestant).[18]

Protestantism[]

The First Baptist Church in America in Providence, Rhode Island (American Baptist Churches USA)

In typical usage, the term mainline is contrasted with evangelical.

The Association of Religion Data Archives (ARDA) counts 26,344,933 members of mainline churches versus 39,930,869 members of evangelical Protestant churches.[19] There is evidence that there has been a shift in membership from mainline denominations to evangelical churches.[20]

As shown in the table below, some denominations with similar names and historical ties to Evangelical groups are considered Mainline.

| Protestant: Mainline vs. Evangelical vs. Traditionally Black Church | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Family: | US %[21] | Examples: | Type: | % of population |

| Baptist | 15.4% | Southern Baptist Convention | Evangelical | 5.3% |

| Independent Baptist, evangelical | Evangelical | 2.5% | ||

| American Baptist Churches in the U.S.A. | Mainline | 1.5% | ||

| National Baptist Convention, USA, Inc. | Black church | 1.4% | ||

| Nondenominational | 6.2% | Nondenominational evangelical | Evangelical | 2.0% |

| Interdenominational evangelical | Evangelical | 0.6% | ||

| Methodist | 4.6% | United Methodist Church | Mainline | 3.6% |

| African Methodist Episcopal Church | Black church | 0.3% | ||

| Pentecostal | 4.6% | Assemblies of God | Evangelical | 1.4% |

| Church of God in Christ | Black church | 0.6% | ||

| Lutheran | 3.5% | Evangelical Lutheran Church in America | Mainline | 1.4% |

| Lutheran Church–Missouri Synod | Evangelical | 1.1% | ||

| Presbyterian/ Reformed |

2.2% | Presbyterian Church (U.S.A.) | Mainline | 0.9% |

| Presbyterian Church in America | Evangelical | 0.4% | ||

| Restorationist | 1.9% | Church of Christ | Evangelical | 1.5% |

| Disciples of Christ | Mainline | <0.3% | ||

| Anglican | 1.3% | Episcopal Church | Mainline | 0.9% |

| Anglican Church in North America | Evangelical | <0.3% | ||

| Holiness | 0.8% | Church of the Nazarene | Evangelical | 0.3% |

| Congregational church | 0.8% | United Church of Christ | Mainline | 0.4% |

| Adventist | 0.6% | Seventh-day Adventist Church | Evangelical | 0.5% |

| Friends (Quakers) | <0.3% | Friends General Conference | Mainline | <0.3% |

Evangelical Protestantism[]

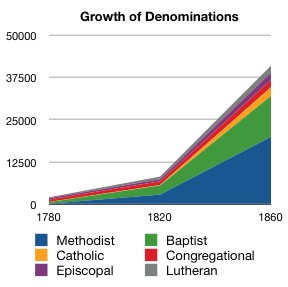

Ever since the Second Great Awakening, Evangelicalism has been very influential. Note the booming membership of Baptist and Methodist churches.

Evangelicalism is a Protestant Christian movement. In typical usage, the term mainline is contrasted with evangelical. Theologically conservative critics accuse the mainline churches of "the substitution of leftist social action for Christian evangelizing, and the disappearance of biblical theology," and maintain that "All the Mainline churches have become essentially the same church: their histories, their theologies, and even much of their practice lost to a uniform vision of social progress."[22] Most adherents consider the key characteristics of evangelicalism to be: a belief in the need for personal conversion (or being "born again"); some expression of the gospel in effort; a high regard for Biblical authority; and an emphasis on the death and resurrection of Jesus.[23] David Bebbington has termed these four distinctive aspects conversionism, activism, biblicism, and crucicentrism, saying, "Together they form a quadrilateral of priorities that is the basis of Evangelicalism."[24]

Note that the term "Evangelical" does not equal Fundamentalist Christianity, although the latter is sometimes regarded simply as the most theologically conservative subset of the former. The major differences largely hinge upon views of how to regard and approach scripture ("Theology of Scripture"), as well as construing its broader world-view implications. While most conservative Evangelicals believe the label has broadened too much beyond its more limiting traditional distinctives, this trend is nonetheless strong enough to create significant ambiguity in the term.[25] As a result, the dichotomy between "evangelical" vs. "mainline" denominations is increasingly complex (particularly with such innovations as the "Emergent Church" movement).

The contemporary North American usage of the term is influenced by the evangelical/fundamentalist controversy of the early 20th century. Evangelicalism may sometimes be perceived as the middle ground between the theological liberalism of the Mainline (Protestant) denominations and the cultural separatism of Fundamentalist Protestantism.[26] Evangelicalism has therefore been described as "the third of the leading strands in American Protestantism, straddl[ing] the divide between fundamentalists and liberals."[27] While the North American perception is important to understand the usage of the term, it by no means dominates a wider global view, where the fundamentalist debate was not so influential.

Evangelicals held the view that the modernist and liberal parties in the Protestant churches had surrendered their heritage as Evangelicals by accommodating the views and values of the world. At the same time, they criticized their fellow Fundamentalists for their separatism and their rejection of the Social Gospel as it had been developed by Protestant activists of the previous century. They charged the modernists with having lost their identity as Evangelicals and the Fundamentalists with having lost the Christ-like heart of Evangelicalism. They argued that the Gospel needed to be reasserted to distinguish it from the innovations of the liberals and the fundamentalists.

They sought allies in denominational churches and liturgical traditions, disregarding views of eschatology and other "non-essentials," and joined also with Trinitarian varieties of Pentecostalism. They believed that in doing so, they were simply re-acquainting Protestantism with its own recent tradition. The movement's aim at the outset was to reclaim the Evangelical heritage in their respective churches, not to begin something new; and for this reason, following their separation from Fundamentalists, the same movement has been better known merely as "Evangelicalism." By the end of the 20th century, this was the most influential development in American Protestant Christianity.

The National Association of Evangelicals is a U.S. agency which coordinates cooperative ministry for its member denominations.

A 2015 global census estimated some 450,000 believers in Christ from a Muslim background in the United States most of whom are evangelicals or Pentecostals.[28]

Mainline Protestantism[]

The National Cathedral (Episcopalian) in Washington, D.C.

The mainline Protestant Christian denominations are those Protestant denominations that were brought to the United States by its historic immigrant groups; for this reason they are sometimes referred to as heritage churches.[29] The largest are the Episcopal (English), Presbyterian (Scottish), Methodist (English and Welsh), and Lutheran (German and Scandinavian) churches.

Mainline Protestantism, including the Episcopalians (76%),[30] the Presbyterians (64%),[30] and the United Church of Christ has the highest number of graduate and post-graduate degrees per capita,[2] of any other Christian denomination in the United States,[31] as well as the most high-income earners.[32]

Episcopalians and Presbyterians tend to be considerably wealthier[33] and better educated than most other religious groups in Americans,[34] and are disproportionately represented in the upper reaches of American business,[35] law and politics, especially the Republican Party.[36] Numbers of the most wealthy and affluent American families as the Vanderbilts and Astors, Rockefeller, Du Pont, Roosevelt, Forbes, Whitney, Morgans, and Harrimans are historically Mainline Protestant families.[33]

According to Scientific Elite: Nobel Laureates in the United States by Harriet Zuckerman, a review of American Nobel prizes winners awarded between 1901 and 1972, 72% of American Nobel Prize Laureates, have identified from a Protestant background.[37] Overall, 84.2% of all the Nobel Prizes awarded to Americans in Chemistry,[37] 60% in Medicine,[37] and 58.6% in Physics[37] between 1901 and 1972 were won by Protestants.

Some of the first colleges and universities in America, including Harvard,[38] Yale,[39] Princeton,[40] Columbia,[41] Dartmouth, Williams, Bowdoin, Middlebury, and Amherst, all were founded by the Mainline Protestantism, as were later Carleton, Duke,[42] Oberlin, Beloit, Pomona, Rollins and Colorado College.

Many mainline denominations teach that the Bible is God's word in function, but tend to be open to new ideas and societal changes.[43] They have been increasingly open to the ordination of women.

Mainline churches tend to belong to organizations such as the National Council of Churches and World Council of Churches.

The seven largest U.S. mainline denominations were called by William Hutchison the "Seven Sisters of American Protestantism"[44][45] in reference to the major liberal groups during the period between 1900 and 1960.

These include:

- United Methodist Church 6,951,278 members (2016)[9]

- Evangelical Lutheran Church in America 3,563,842 members (2016)[46]

- Episcopal Church in the United States of America 1,779,335 active baptized members (2015)[47]

- Presbyterian Church (USA) 1,482,767 active members (2016)[48]

- American Baptist Churches in the USA 1,198,046 members (2014)[49]

- United Church of Christ 880,383 members (2016)[50]

- Christian Church (Disciples of Christ) 497,423 (2014)[51]

The Association of Religion Data Archives also considers these denominations to be mainline:[19]

- Religious Society of Friends (Quakers) 108,500 members

- Reformed Church in America 223,675 members (2015)

- International Council of Community Churches 68,300 members (2010)[52]

- National Association of Congregational Christian Churches 65,569 members (2000)[53]

- North American Baptist Conference 47,150 members (2006)[54]

- Moravian Church in America, Southern Province 21,513 members (1991)[55]

- Moravian Church in America, Northern Province 20,220 members (2010)[56]

- Universal Fellowship of Metropolitan Community Churches 15,666 members (2006)[57]

- Latvian Evangelical Lutheran Church in America 12,000 members (2007)

- Congregational Christian Churches, (not part of any national CCC body)

- Moravian Church in America, Alaska Province

The Association of Religion Data Archives has difficulties collecting data on traditionally African American denominations. Those churches most likely to be identified as mainline include these Methodist groups:

- African Methodist Episcopal Church

- Christian Methodist Episcopal Church

Catholic Church[]

The Basilica of the National Shrine of the Immaculate Conception in Washington, D.C. is the largest Catholic church in the United States.

The Catholic Church arrived in what is now the United States during the earliest days of the European colonization of the Americas. At the time the country was founded (meaning the Thirteen Colonies in 1776), only a small fraction of the population there were Catholics (mostly in Maryland); however, as a result of expansion and immigration over the country's history, the number of adherents has grown dramatically and it is the largest profession of faith in the United States today. With over 67 million registered residents professing the faith in 2008, the United States has the fourth largest Catholic population in the world after Brazil, Mexico, and the Philippines, respectively.

The Church's leadership body in the United States is the United States Conference of Catholic Bishops, made up of the hierarchy of bishops and archbishops of the United States and the U.S. Virgin Islands, although each bishop is independent in his own diocese, answerable only to the Pope.

No primate for Catholics exists in the United States. The Archdiocese of Baltimore has Prerogative of Place, which confers to its archbishop a subset of the leadership responsibilities granted to primates in other countries.

The number of Catholics grew from the early 19th century through immigration and the acquisition of the predominantly Catholic former possessions of France, Spain, and Mexico, followed in the mid-19th century by a rapid influx of Irish, German, Italian and Polish immigrants from Europe, making Catholicism the largest Christian denomination in the United States. This increase was met by widespread prejudice and hostility, often resulting in riots and the burning of churches, convents, and seminaries.[58] The integration of Catholics into American society was marked by the election of John F. Kennedy as President in 1960. Since then, the percentage of Americans who are Catholic has remained at around 25%.[59]

According to the Association of Catholic Colleges and Universities in 2011, there are approximately 230 Roman Catholic universities and colleges in the United States with nearly 1 million students and some 65,000 professors.[60] Catholic schools educate 2.7 million students in the United States, employing 150,000 teachers. In 2002, Catholic health care systems, overseeing 625 hospitals with a combined revenue of 30 billion dollars, comprised the nation's largest group of nonprofit systems.[61]

Eastern Orthodox Christianity[]

St. Nicholas Cathedral in Washington, D.C., is the primary cathedral of the Orthodox Church in America.

Groups of immigrants from several different regions, mainly Eastern Europe and the Middle East, brought Eastern Orthodoxy to the United States.[62] This traditional branch of Eastern Christianity has since spread beyond the boundaries of ethnic immigrant communities and now include multi-ethnic membership and parishes. There are several Eastern Orthodox ecclesiastical jurisdictions in the USA, organized within the Assembly of Canonical Orthodox Bishops of the United States of America.[63] Statistically, Eastern Orthodox Christians are among the wealthiest Christians denomination in the United States,[32] and they also tend to be better educated than most other religious groups in America, in the sense that they have a high number of graduate (68%) and post-graduate degrees (28%) per capita.[31]

Oriental Orthodox Christianity[]

Several groups of Christian immigrants, mainly from the Middle East, Caucasus, Africa and India, brought Oriental Orthodoxy to the United States.[64] This ancient branch of Eastern Christianity includes several ecclesiastical jurisdictions in the USA, like Armenian Apostolic Church in the United States,[65] and Coptic Orthodox Church in the United States.[66] There are also dioceses of the Ethiopian Orthodox Church, and Syriac Orthodox Church,[67] including Malankara Archdiocese of North America. Also, there are dioceses of the Malankara Orthodox Syrian Church in the USA (Malankara Orthodox Diocese of Northeast America and Malankara Orthodox Diocese of Southwest America).

Latter-day Saint Movement[]

The Salt Lake Temple, which took 40 years to build, is one of the most iconic images of the LDS Church.

The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (LDS Church) is a nontrinitarian restorationist denomination. The church is headquartered in Salt Lake City, and is the largest originating from the Latter Day Saint movement which was founded by Joseph Smith in Upstate New York in 1830. It forms the majority in Utah, the plurality in Idaho, and high percentages in Nevada, Arizona, and Wyoming; in addition to sizable numbers in Colorado, Montana, Washington, Oregon, Alaska, Hawaii and California. Current membership in the U.S. is 6.6 million and total membership is 16.1 million worldwide.[68]

In 2010, around 13-14% of Latter Day Saints lived in Utah, the center of cultural influence for Mormonism.[69] Utah Latter Day Saints (as well as Latter Day Saints living in the Intermountain West) are on average more culturally and politically conservative and Libertarian than those living in some cosmopolitan centers elsewhere in the U.S.[70] Utahns self-identifying as Latter Day Saints also attend church somewhat more on average than Latter Day Saints living in other states. (Nonetheless, whether they live in Utah or elsewhere in the U.S., Latter Day Saints tend to be more culturally and politically conservative than members of other U.S. religious groups.)[71] Utah Latter Day Saints often place a greater emphasis on pioneer heritage than international Latter Day Saints who generally are not descendants of the Mormon pioneers.[72]

Community of Christ (formerly the Reorganized Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints) is a trinitarian restorationist denomination based in Independence, Missouri at the theologically significant Temple Lot. Community of Christ is the second largest denomination in the Latter-day Saint movement with 130,000 members in the United States and 250,000 worldwide (See Community of Christ membership statistics). The church owns many of the early LDS historic sites including the Kirtland Temple near Cleveland, Ohio and the Joseph Smith properties in Nauvoo, Illinois. Community of Christ has taken an ecumenical and progressive approach recent years including joining the National Council of Churches, ordaining women to the church's priesthood since 1984, and more recently approving the blessing of same-sex marriages.

Small churches within the Latter-day Saint movement include Church of Christ (Temple Lot), Fundamentalist Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, Restoration Branches, and Remnant Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints.

History[]

Youth programs[]

Demographics[]

Demographics by state[]

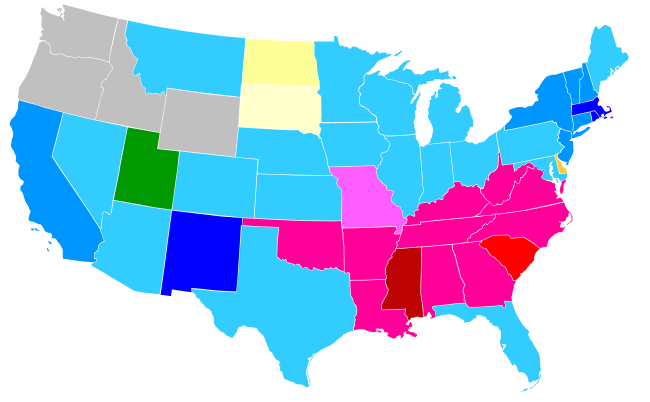

| <30% | <40% | <50% | >50% | |

| Catholic | ||||

| Baptist | ||||

| Methodist | ||||

| Lutheran | ||||

| Mormon | ||||

| No religion |

Beliefs and attitudes[]

The Baylor University Institute for Studies of Religion conducted a survey covering various aspects of American religious life.[74] The researchers analyzing the survey results have categorized the responses into what they call the "four Gods": An authoritarian God (31%), a benevolent God (25%), a distant God (23%), and a critical God (16%).[74] A major implication to emerge from this survey is that "the type of god people believe in can predict their political and moral attitudes more so than just looking at their religious tradition."[74]

As far as religious tradition, the survey determined that 33.6% of respondents are evangelical Protestants, while 10.8% had no religious affiliation at all. Out of those without affiliation, 62.9% still indicated that they "believe in God or some higher power".[74]

Another study, conducted by Christianity Today with Leadership magazine, attempted to understand the range and differences among American Christians. A national attitudinal and behavioral survey found that their beliefs and practices clustered into five distinct segments. Spiritual growth for two large segments of Christians may be occurring in non-traditional ways. Instead of attending church on Sunday mornings, many opt for personal, individual ways to stretch themselves spiritually.[75]

- 19 percent of American Christians are described by the researchers as Active Christians. They believe salvation comes through Jesus Christ, attend church regularly, are Bible readers, invest in personal faith development through their church, accept leadership positions in their church, and believe they are obligated to "share [their] faith", that is, to evangelize others.

- 20 percent are referred to as Professing Christians. They are also committed to "accepting Christ as Savior and Lord" as the key to being a Christian, but focus more on personal relationships with God and Jesus than on church, Bible reading or evangelizing.

- 16 percent fall into a category named Liturgical Christians. They are predominantly Lutheran, Catholic, Episcopalian, Eastern Orthodox or Oriental Orthodox. They are regular churchgoers, have a high level of spiritual activity and recognize the authority of the church.

- 24 percent are considered Private Christians. They own a Bible but don't tend to read it. Only about one-third attend church at all. They believe in God and in doing good things, but not necessarily within a church context. This was the largest and youngest segment. Almost none are church leaders.

- 21 percent in the research are called Cultural Christians. These do not view Jesus as essential to salvation. They exhibit little outward religious behavior or attitudes. They favor a universality theology that sees many ways to God. Yet, they clearly consider themselves to be Christians.

Church attendance[]

Gallup International indicates that 41%[76] of American citizens report they regularly attend religious services, compared to 15% of French citizens, 10% of UK citizens,[77] and 7.5% of Australian citizens.[78]

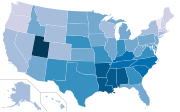

By state[]

Percent of Americans who report attending religious services at least weekly in 2014.

Church attendance varies significantly by state and region. In a 2014 Gallup survey, less than half of Americans said that they attended church or synagogue weekly. The figures ranged from 51% in Utah to 17% in Vermont.[79]

| Rank | State | Percent |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 51% | |

| 2 | 47% | |

| 3 | 46% | |

| 3 | 46% | |

| 5 | 45% | |

| 6 | 42% | |

| 6 | 42% | |

| 8 | 41% | |

| 9 | 40% | |

| 10 | 39% | |

| 10 | 39% | |

| 10 | 39% | |

| 13 | 36% | |

| 14 | 35% | |

| 14 | 35% | |

| 14 | 35% | |

| 14 | 35% | |

| 14 | 35% | |

| 19 | 34% | |

| 19 | 34% | |

| 21 | 33% | |

| 21 | 33% | |

| 21 | 32% | |

| 21 | 32% | |

| 21 | 32% | |

| 21 | 32% | |

| 21 | 32% | |

| 21 | 32% | |

| 21 | 32% | |

| 30 | 31% | |

| 30 | 31% | |

| 30 | 31% | |

| 33 | 30% | |

| 34 | 29% | |

| 35 | 28% | |

| 35 | 28% | |

| 35 | 28% | |

| 38 | 27% | |

| 38 | 27% | |

| 38 | 27% | |

| 41 | 26% | |

| 42 | 25% | |

| 42 | 25% | |

| 42 | 25% | |

| 45 | 24% | |

| 45 | 24% | |

| 47 | 23% | |

| 48 | 22% | |

| 49 | 20% | |

| 49 | 20% | |

| 51 | 17% |

Race[]

Data from the Pew Research Center show that as of 2008, the majority of White Americans were Christian, and about 51% of the White American were Protestant, and 26% were Catholic.

The most methodologically rigorous study of Hispanic and Latino Americans religious affiliation to date was the Hispanic Churches in American Public Life (HCAPL) National Survey, conducted between August and October 2000. This survey found that 70% of all Hispanic and Latino Americans are Catholic, 20% are Protestant, 3% are "alternative Christians" (such as Mormon or Jehovah's Witnesses).[80]

The majority of African Americans are Protestant (78%), many of whom follow the historically black churches.[81][82] A 2012 Pew Research Center study found that 42% of the Asian Americans identify themselves as Christians.[83]

Ethnicity[]

Beginning around 1600, Northern European settlers introduced Anglican and Puritan religion, as well as Baptist, Presbyterian, Lutheran, Quaker, and Moravian denominations.[84]

Beginning in the 16th century, the Spanish (and later the French and English) introduced Catholicism. From the 19th century to the present, Catholics came to the US in large numbers due to the immigration of Italians, Hispanics, Portuguese, French, Polish, Irish, Highland Scots, Dutch, Flemish, Hungarians, Germans, Lebanese (Maronite), and other ethnic groups.

Most of the Eastern Orthodox adherents in the United States are descended from immigrants of Eastern European or Middle Eastern background, especially from Greek, Russian, Ukrainian, Arab, Bulgarian, Romanian, or Serbian backgrounds.[62][85]

Most of the Oriental Orthodox adherents in the United States are from Armenian, Coptic and Ethiopian backgrounds.[64]

Most of the traditional Church of the East adherents in the United States are from Assyrian background.

Data from the Pew Research Center show that as of 2013, there were about 1.6 million Christians from Jewish background, most of them Protestant.[86][87][88] According to the same data, most of the Christians of Jewish descent were raised as Jews or are Jews by ancestry.[87]

Conversion[]

A study from 2015 estimated some 450,000 American Muslims who had converted to Christianity, most of whom belong to an evangelical or Pentecostal community.[28] In 2010 there were approximately 180,000 Arab-Americans and about 130,000 Iranian Americans who converted from Islam to Christianity. Dudley Woodbury, a Fulbright scholar of Islam, estimates that 20,000 Muslims convert to Christianity annually in the United States.[89]

It's been also reported that conversion into Christianity is significantly increasing among Korean Americans,[90] Chinese Americans,[91] and Japanese Americans.[92] By 2012, the percentage of Christians within the mentioned communities was 71%,[93] more than 30%[94] and 37%.[95]

Messianic Judaism (or Messianic Movement) is the name of a Protestant movement comprising a number of streams, whose members may consider themselves Jewish.[96] It blends elements of religious Jewish practice with evangelical Protestantism. Messianic Judaism affirms Christian creeds such as the messiahship and divinity of "Yeshua" (the Hebrew name of Jesus) and the Triune Nature of God, while also adhering to some Jewish dietary laws and customs. As of 2012, population estimates for the United States were between 175,000 and 250,000 members.[97]

Self-reported membership statistics[]

See also[]

- Demographics of the United States

- History of religion in the United States

- Religion in the United States

- Yearbook of American and Canadian Churches

References[]

- ^ Newport, Frank (25 December 2015). "Percentage of Christians in U.S. Drifting Down, but Still High". http://www.gallup.com/poll/187955/percentage-christians-drifting-down-high.aspx.

- ^ a b "America's Changing Religious Landscape". Pew Research Center: Religion & Public Life. May 12, 2015. http://www.pewforum.org/2015/05/12/americas-changing-religious-landscape/.

- ^ "American Religious Identification Survey". CUNY Graduate Center. 2001. Archived from the original on 2011-07-09. https://web.archive.org/web/20110709082644/http://www.gc.cuny.edu/faculty/research_briefs/aris/key_findings.htm. Retrieved 2007-06-17.

- ^ "'Nones' on the Rise". Pew Research Center: Religion & Public Life. October 9, 2012. http://www.pewforum.org/2012/10/09/nones-on-the-rise/.

- ^ Finke, Roger; Rodney Stark (2005). The Churching of America, 1776-2005. Rutgers University Press. pp. 22–23. ISBN 0-8135-3553-0. online at Google Books.

- ^ Pew Forum on Religion and Public Life. U.S. Religious Landscape Survey: Religious Affiliation: Diverse and Dynamic. February 2008, pp. 5, 12. Accessed February 8, 2011.

- ^ a b Green, John C. "The American Religious Landscape and Political Attitudes: A Baseline for 2004". University of Akron. Archived from the original on 21 June 2005. https://web.archive.org/web/20050621001046/http://www.uakron.edu/bliss/docs/Religious_Landscape_2004.pdf. Retrieved 2007-06-18.

- ^ a b "Trends continue in church membership growth or decline", Yearbook of American & Canadian Churches, US: National Council of Churches, February 14, 2011, http://www.ncccusa.org/news/110210yearbook2011.html, retrieved May 14, 2017

- ^ a b Communications, United Methodist. "Statistical Resources - The United Methodist Church" (in en). http://www.gcfa.org/data-services-statistics.

- ^ Mitt Romney's Mormon roots in northern England retrieved 16 June 2012

- ^ Mormonism beginnings retrieved 15 June 2012

- ^ "ARDA Sources for Religious Congregations & Membership Data". ARDA. 2000. http://www.thearda.com/mapsReports/rcms_notes.asp. Retrieved 2010-05-29.

- ^ Tri-Faith America: How Catholics and Jews Held Postwar America to Its Protestant Promise by Kevin M. Schultz, p. 9

- ^ Obligations of Citizenship and Demands of Faith: Religious Accommodation in Pluralist Democracies by Nancy L. Rosenblum, Princeton University Press, 2000 - 438, p. 156

- ^ The Protestant Voice in American Pluralism by Martin E. Marty, chapter 1

- ^ "10 facts about religion in America". 27 August 2015. http://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2015/08/27/10-facts-about-religion-in-america/.

- ^ God's Continent: Christianity, Islam, and Europe's Religious Crisis, p 284, Philip Jenkins - 2007

- ^ The figures for this 2007 abstract are based on surveies for 1990 and 2001 from the Graduate School and University Center at the City University of New York. Kosmin, Barry A.; Egon Mayer; Ariela Keysar (2001). "American Religious Identification Survey". City University of New York.; Graduate School and University Center. Archived from the original on 2007-06-14. https://web.archive.org/web/20070614124201/http://www.trincoll.edu/NR/rdonlyres/AFCEF53A-8DAB-4CD9-A892-5453E336D35D/0/NEWARISrevised121901b.pdf. Retrieved 2007-04-04.

- ^ a b "The Association of Religion Data Archives - Maps and Reports - Reports - Denomination Listing: Mainline". http://www.thearda.com/mapsReports/reports/mainline.asp. Retrieved 5 March 2015.

- ^ "The U.S. Church Finance Market: 2005-2010" Non-denominational membership doubled between 1990 and 2001. (April 1, 2006, report)

- ^ "America's Changing Religious Landscape, Appendix B: Classification of Protestant Denominations". Pew Research Center. 12 May 2015. http://www.pewforum.org/2015/05/12/appendix-b-classification-of-protestant-denominations/. Retrieved 15 May 2018.

- ^ The Death of Protestant America: A Political Theory of the Protestant Mainline by Joseph Bottum, First Things (August/September 2008)[1]

- ^ Eskridge, Larry (1995). "Defining Evangelicalism". Institute for the Study of American Evangelicals. http://www.wheaton.edu/isae/defining_evangelicalism.html. Retrieved 2008-03-04.

- ^ Bebbington, p. 3.

- ^ George Marsden Understanding Fundamentalism and Evangelicalism Eerdmans, 1991.

- ^ Luo, Michael (2006-04-16). "Evangelicals Debate the Meaning of 'Evangelical'". The New York Times (nytimes.com). https://www.nytimes.com/2006/04/16/weekinreview/16luo.html?_r=1&adxnnlx=1145227368-p%20hJwvCXS0qceSTw%20jLi8w&pagewanted=all.

- ^ Mead, Walter Russell (2006). "God's Country?". Foreign Affairs. Council on Foreign Relations. http://www.foreignaffairs.org/20060901faessay85504-p20/walter-russell-mead/god-s-country.html. Retrieved 2008-03-27.

- ^ a b (2015) "Believers in Christ from a Muslim Background: A Global Census". IJRR 11 (10). Retrieved on 14 February 2016.

- ^ The Death of Protestant America: A Political Theory of the Protestant Mainline by Joseph Bottum, First Things (August/September 2008)[2]

- ^ a b Leonhardt, David. "Faith, Education and Income". https://economix.blogs.nytimes.com/2011/05/13/faith-education-and-income/?_r=1.

- ^ a b (PDF) US Religious Landscape Survey: Diverse and Dynamic, The Pew Forum, February 2008, p. 85, http://religions.pewforum.org/pdf/report-religious-landscape-study-full.pdf, retrieved 2012-09-17

- ^ a b Leonhardt, David (2011-05-13). "Faith, Education and Income". The New York Times. https://economix.blogs.nytimes.com/2011/05/13/faith-education-and-income/. Retrieved May 13, 2011.

- ^ a b B.DRUMMOND AYRES Jr. (2011-12-19). "THE EPISCOPALIANS: AN AMERICAN ELITE WITH ROOTS GOING BACK TO JAMESTOWN". New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/1981/04/28/us/the-episcopalians-an-american-elite-with-roots-going-back-to-jamestown.html. Retrieved 2012-08-17.

- ^ Irving Lewis Allen, "WASP—From Sociological Concept to Epithet," Ethnicity, 1975 154+

- ^ Hacker, Andrew (1957). "Liberal Democracy and Social Control". American Political Science Review 51 (4): 1009–1026 [p. 1011].

- ^ Baltzell (1964). The Protestant Establishment. p. 9.

- ^ a b c d Harriet Zuckerman, Scientific Elite: Nobel Laureates in the United States New York, The Free Pres, 1977, p.68: Protestants turn up among the American-reared laureates in slightly greater proportion to their numbers in the general population. Thus 72 percent of the seventy-one laureates but about two thirds of the American population were reared in one or another Protestant denomination-)

- ^ "The Harvard Guide: The Early History of Harvard University". News.harvard.edu. http://www.news.harvard.edu/guide/intro/index.html. Retrieved 2010-08-29.

- ^ "Increase Mather". http://college.hmco.com/history/readerscomp/rcah/html/ah_057300_matherincrea.htm., Encyclopædia Britannica Eleventh Edition, Encyclopædia Britannica

- ^ Princeton University Office of Communications. "Princeton in the American Revolution". http://www.princeton.edu/pr/facts/revolution.html. Retrieved 2011-05-24. The original Trustees of Princeton University "were acting in behalf of the evangelical or New Light wing of the Presbyterian Church, but the College had no legal or constitutional identification with that denomination. Its doors were to be open to all students, 'any different sentiments in religion notwithstanding.'"

- ^ McCaughey, Robert (2003). Stand, Columbia : A History of Columbia University in the City of New York. New York, New York: Columbia University Press. p. 1. ISBN 0231130082.

- ^ "Duke University's Relation to the Methodist Church: the basics". Duke University. 2002. http://library.duke.edu/uarchives/history/duke-umchh-basic.html. Retrieved 2010-03-27. "Duke University has historical, formal, on-going, and symbolic ties with Methodism, but is an independent and non-sectarian institution ... Duke would not be the institution it is today without its ties to the Methodist Church. However, the Methodist Church does not own or direct the University. Duke is and has developed as a private non-profit corporation which is owned and governed by an autonomous and self-perpetuating Board of Trustees."

- ^ "The Decline of Mainline Protestantism". http://www.ecai.org/nara/nara_article.html.

- ^ Protestant Establishment I (Craigville Conference) Archived September 28, 2007, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Hutchison, William. Between the Times: The Travail of the Protestant Establishment in America, 1900-1960 (1989), Cambridge U. Press, ISBN 0-521-40601-3

- ^ "ELCA Facts" (in en). ELCA.org. http://www.elca.org/News-and-Events/ELCA-Facts. Retrieved 2017-09-06.

- ^ (PDF) Table of Statistics of the Episcopal Church From 2015 Parochial Reports, The Episcopal Church, 2017, p. 3, https://www.episcopalchurch.org/files/table_of_statistics_english_2015.pdf, retrieved 2017-09-06

- ^ "SUMMARIES OF STATISTICS – COMPARATIVE SUMMARIES" (PDF). http://www.pcusa.org/site_media/media/uploads/oga/pdf/2016_comparative_summaries_.pdf. Retrieved September 6, 2017.

- ^ "ABC USA Summary of Statistics". December 2014. http://www.abc-usa.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/06/Regional-Giving-and-Church-Statistics-Reported-for-the-Year-Ending-in-2014.pdf.

- ^ "The United Church Of Christ: A Statistical Profile". Fall 2017. http://uccfiles.com/pdf/2017-UCC-Statistical-Profile.pdf/.

- ^ "2014 Christian Church (D.O.C.) Yearbook and Directory Membership Statistics". http://derekpenwell.net/the-company-of-the-eudaimon/2014/8/26/2014-christian-church-doc-yearbook-and-directory-membership-statistics.

- ^ "International Council of Community Churches- Religious Groups - The Association of Religion Data Archives". http://www.thearda.com/Denoms/D_1313.asp. Retrieved 26 February 2018.

- ^ "National Association of Congregational Christian Churches- Religious Groups - The Association of Religion Data Archives". http://www.thearda.com/Denoms/D_1462.asp. Retrieved 5 March 2015.

- ^ North American Baptist Conference - Membership Data ARDA

- ^ "Moravian Church in America (Unitas Fratrum), Southern Province- Religious Groups - The Association of Religion Data Archives". http://www.thearda.com/Denoms/D_1335.asp. Retrieved 5 March 2015.

- ^ "Moravian Church in America (Unitas Fratrum), Northern Province- Religious Groups - The Association of Religion Data Archives". http://www.thearda.com/Denoms/D_1334.asp. Retrieved 6 March 2018.

- ^ "Universal Fellowship of Metropolitan Community Churches- Religious Groups - The Association of Religion Data Archives". http://www.thearda.com/Denoms/D_1142.asp. Retrieved 5 March 2015.

- ^ J. A. Birkhaeuser, [3] "1893 History of the church: from its first establishment to our own times. Designed for the use of ecclesiastical seminaries and colleges, Volume 3"

- ^ "Is the Bottom Really Falling Out of Catholic Mass Attendance? A Recent CARA Survey Ponders the Question - Community in Mission". 15 December 2010. http://blog.adw.org/2010/12/is-the-bottom-really-falling-out-of-catholic-mass-attendance-a-recent-cara-survey-ponders-the-question/.

- ^ Jerry Filteau, "Higher education leaders commit to strengthening Catholic identity," NATIONAL CATHOLIC REPORTER, Vol 47, No. 9, Feb. 18, 2011, 1

- ^ Arthur Jones, "Catholic health care aims to make 'Catholic' a brand name," National Catholic Reporter 18 July 2003, 8.

- ^ a b FitzGerald 2007, p. 269-276.

- ^ Assembly of Canonical Orthodox Bishops of the United States of America

- ^ a b FitzGerald 2007, p. 277-279.

- ^ The Armenian Church of America

- ^ Coptic Churches in the United States and Canada

- ^ Syriac Orthodox Church of Antioch

- ^ "LDS Statistics and Church Facts - Total Church Membership". http://www.mormonnewsroom.org/facts-and-statistics/country/united-states/.

- ^ "USA–Utah". LDS Newsroom. http://newsroom.lds.org/country/usa-utah. Retrieved November 11, 2011..

- ^ Mauss often compares Salt Lake City Latter Day Saints to California Latter Day Saints from San Francisco and East Bay. The Utah Latter Day Saints were generally more orthodox and conservative. Mauss (1994, pp. 40, 128); (July 24, 2009) "A Portrait of Latter Day Saints in the U.S.: III. Social and Political Views". .

- ^ Newport, Frank (January 11, 2010). "Latter Day Saints Most Conservative Major Religious Group in U.S.: Six out of 10 latter Day Saints are politically conservative". ; Pond, Allison (July 24, 2009). "A Portrait of latter Day Saints in the U.S". .

- ^ Thomas W. Murphy (1996). "Reinventing Mormonism: Guatemala as Harbinger of the Future?". Dialogue: A Journal of Mormon Thought. https://dialoguejournal.com/wp-content/uploads/sbi/articles/Dialogue_V29N01_183.pdf. Retrieved November 11, 2011.

- ^ Religious Congregations and Membership in the United States, 2000. Collected by the Association of Statisticians of American Religious Bodies (ASARB) and distributed by the Association of Religion Data Archives.

- ^ a b c d "Losing My Religion? No, Says Baylor Religion Survey". Baylor University. September 11, 2006. http://www.baylor.edu/pr/news.php?action=story&story=41678.

- ^ "5 Kinds of Christians — Understanding the disparity of those who call themselves Christian in America. Leadership Journal, Fall 2007.

- ^ "How many people go regularly to weekly religious services?". Religious Tolerance website. http://www.religioustolerance.org/rel_rate.htm.

- ^ "'One in 10' attends church weekly". BBC News. 3 April 2007. http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/uk/6520463.stm.

- ^ NCLS releases latest estimates of church attendance, National Church Life Survey, Media release

- ^ a b Inc., Gallup,. "Frequent Church Attendance Highest in Utah, Lowest in Vermont". http://www.gallup.com/poll/181601/frequent-church-attendance-highest-utah-lowest-vermont.aspx.

- ^ "Latinos and the Transformation of american religion". http://www.pewforum.org/files/2007/04/hispanics-religion-07-final-mar08.pdf. Retrieved 2014-10-11.

- ^ "Pew Forum: A Religious Portrait of African-Americans". The Pew Forum on Religion & Public Life. January 30, 2009. http://www.pewforum.org/A-Religious-Portrait-of-African-Americans.aspx. Retrieved October 31, 2012.

- ^ U.S.Religious Landscape Survey p.40 The Pew Forum on Religion and Public Life (February 2008). Retrieved July 20, 2009.

- ^ "Asian Americans: A Mosaic of Faiths" (overview) (Archive). Pew Research. July 19, 2012. Retrieved on May 3, 2014.

- ^ Sydney E. Ahlstrom, A religious history of the American people (1976) pp 121-59 .

- ^ Alexei D. Krindatch, ed., Atlas of American Orthodox Christian Churches (Holy Cross Orthodox Press, 2011) online.

- ^ "How many Jews are there in the United States?". Pew Research Center. http://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2013/10/02/how-many-jews-are-there-in-the-united-states/.

- ^ a b "A PORTRAIT OF JEWISH AMERICANS: Chapter 1: Population Estimates". Pew Research Center. http://www.pewforum.org/2013/10/01/chapter-1-population-estimates/.

- ^ "American-Jewish Population Rises to 6.8 Million". haaretz. http://www.haaretz.com/jewish/news/.premium-1.549713.

- ^ "Why Are Millions of Muslims Becoming Christian?". http://www.ncregister.com/daily-news/why-are-millions-of-muslims-becoming-christian/.

- ^ Yoo, David; Ruth H. Chung (2008). Religion and spirituality in Korean America. University of Illinois Press. ISBN 978-0-252-07474-5.

- ^ "Leave China, Study in America, Find Jesus". https://foreignpolicy.com/2016/02/11/leave-china-study-in-america-find-jesus-chinese-christian-converts-at-american-universities/.

- ^ Brian Niiya (1993). Japanese American History: An A-To-Z Reference from 1868 to the Present. VNR AG. p. 28. https://books.google.com/books?id=QZg6Ft_jvJ0C&pg=RA1-PA28.

- ^ "Pew Forum - Korean Americans' Religions". Projects.pewforum.org. 2012-07-18. http://projects.pewforum.org/2012/07/18/religious-affiliation-of-asian-americans-2/asianamericans_affiliation-8-2/. Retrieved 2013-02-16.

- ^ Pew Forum - Chinese Americans' Religions.

- ^ "Japanese Americans - Pew Forum on Religion & Public Life". http://projects.pewforum.org/2012/07/18/religious-affiliation-of-asian-americans-2/asianamericans_affiliation-9-2/. Retrieved March 17, 2015.

- ^ Ariel, Yaakov S. (2000). "Chapter 20: The Rise of Messianic Judaism" (Google Books). Evangelizing the chosen people: missions to the Jews in America, 1880–2000. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press. p. 223. ISBN 978-0-8078-4880-7. OCLC 43708450. https://books.google.com/books?id=r3hCgIZB790C&printsec=frontcover&vq=advocated+offspring+rhetoric+Shalom#v=onepage&q=advocated%20offspring%20rhetoric%20Shalom&f=false. Retrieved August 10, 2010.

- ^ Posner, Sarah (November 29, 2012). "Kosher Jesus: Messianic Jews in the Holy Land". The Atlantic.

Sources[]

- FitzGerald, Thomas (2007). "Eastern Christianity in the United States". The Blackwell Companion to Eastern Christianity. Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishing. pp. 269-279. https://books.google.com/books?id=fHtSuvaVAAoC.

Further reading[]

- Ahlstrom, Sydney E. A Religious History of the American People (1972, 2004) the standard history excerpt and text search

- Askew, Thomas A., and Peter W. Spellman. The Churches and the American Experiment: Ideals and Institutions, (1984).

- Balmer, Randall. Protestantism in America (2005)

- Balmer, Randall. The Encyclopedia of Evangelicalism (2002) excerpt and text search

- Bonomi, Patricia U. Under the Cope of Heaven: Religion, Society, and Politics in Colonial America Oxford University Press, 1988 online edition

- Butler, Jon, et al. Religion in American Life: A Short History (2011)

- Dolan, Jay P. The American Catholic Experience (1992)

- Johnson, Paul, ed. African-American Christianity: Essays in History, (1994) complete text online free

- Keller, Rosemary Skinner, and Rosemary Radford Ruether, eds. Encyclopedia of Women and Religion in North America (3 vol 2006)

- Noll, Mark A. American Evangelical Christianity: An Introduction (2000) excerpt and text search

- Wigger, John H.. and Nathan O. Hatch. Methodism and the Shaping of American Culture. (2001) excerpt and text search

External links[]

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||