Charlemagne ( /ˈʃɑrl

ɪmeɪn/; Latin: Carolus Magnus or Karolus Magnus, meaning Charles the Great; possibly 742 –28th of January 814) was King of the Franks from 768 and Emperor of the Romans (Imperator Romanorum) from 800 to his death in 814. He expanded the Frankish kingdom into an empire that incorporated much of Western and Central Europe. During his reign, he conquered Italy and was crowned Imperator Augustus by Pope Leo III on 25 December 800. This temporarily made him a rival of the Byzantine Emperor in Constantinople. His rule is also associated with the Carolingian Renaissance, a revival of art, religion, and culture through the medium of the Catholic Church. Through his foreign conquests and internal reforms, Charlemagne helped define both Western Europe and the Middle Ages. He is numbered as Charles I in the regnal lists of Germany (where he is known as Karl der Große), the Holy Roman Empire, and France.

The son of King Pippin the Short and Bertrada of Laon, his original name in the Frankish language was never recorded, but early instances of his name in Latin read "Carolos" or "Karol's". He succeeded his father and co-ruled with his brother Carloman until the latter's death in 771. Charlemagne continued the policy of his father towards the papacy and became its protector, removing the Lombards from power in Italy, and waging war on the Saracens who menaced his realm from Spain. It was during one of these campaigns that he experienced the worst defeat of his life at Roncesvalles (778). He also campaigned against the peoples to his east, especially the Saxons, and after a protracted war subjected them to his rule. By converting them to Christianity, he integrated them into his realm and thus paved the way for the later Ottonian Dynasty.

Today regarded as the founding father of both France and Germany and sometimes as the Father of Europe, as he was the first ruler of a united Western Europe since the fall of the Roman Empire.[1]

Background

| Carolingian dynasty |

Pippinids

|

Arnulfings

|

Carolingians

|

After the Treaty of Verdun (843)

|

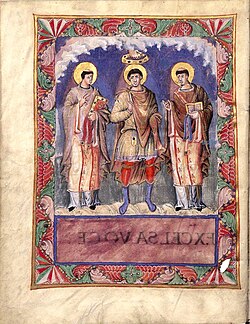

A Frankish king (center), like Charlemagne, depicted in the Sacramentary of Charles the Bald (about 870).

By the 6th century the Franks were Christianised, and the Frankish Empire ruled by the Merovingians had become the most powerful of the kingdoms which succeeded the Western Roman Empire. But following the Battle of Tertry, the Merovingians declined into a state of powerlessness, for which they have been dubbed do-nothing kings(French: rois fainéants). Practically all government powers of any consequence were exercised by their chief officer, the mayor of the palace or major domus.

In 687, Pepin of Herstal, mayor of the palace of Austrasia, ended the strife between various kings and their mayors with his victory at Tertry and practically became the sole governor of the entire Frankish kingdom. Pepin himself was the grandson of two most important figures of the Austrasian Kingdom, Saint Arnulf of Metz and Pepin of Landen. Pepin the Middle was eventually succeeded by his illegitimate son Charles, later known as Charles Martel (the Hammer). After 737, Charles governed the Franks without a king on the throne but desisted from calling himself "king". Charles was succeeded by his sons Carloman and Pepin the Short, the father of Charlemagne. To curb separatism in the periphery of the realm, the brothers placed Childeric III on the throne, who was to be the last Merovingian king.

After Carloman resigned his office, Pepin had Childeric III deposed with Pope Zachary's approval. In 751, Pepin was elected and anointed King of the Franks and in 754, Pope Stephen II again anointed him and his young sons. Thus was the Merovingian dynasty replaced by the Carolingian dynasty, named after Pippin's father Charles Martel and its most famous member, Charlemagne.

Pippin's sons, Charlemagne and Carloman, immediately became joint heirs to the great realm which already covered most of western and central Europe. Under the new dynasty, the Frankish kingdom spread to encompass an area including most of Western Europe. The division of that kingdom formed France and Germany;[2] and the religious, political, and artistic evolutions originating from a centrally-positioned Francia made a defining imprint on the whole of Western Europe. The foundations of Europe—as more than a geographic entity—were laid in the Dark Ages, largely out of the Frankish Empire.

Date and place of birth

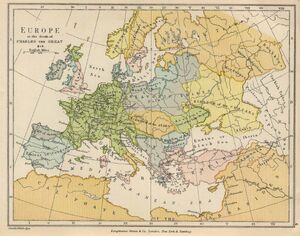

Map of Europe at the time of his death.

Charlemagne's birthday was believed to be April 2, 742; however several factors led to reconsideration of this traditional date. First, the year 742 was calculated from his age given at death, rather than attestation within primary sources. Another date is given in the Annales Petarienses, April 1, 747. In that year, April 1 is Easter. The birth of an emperor on Easter is a coincidence likely to provoke comment, but there is no such comment documented in 747, leading some to suspect that the Easter birthday was a pious fiction concocted as a way of honoring the Emperor. Other commentators weighing the primary records have suggested that the birth was one year later, 748. At present, it is impossible to be certain of the date of the birth of Charlemagne. The best guesses include April 1, 747, after April 15, 747, or April 1, 748, in Herstal (where his father was born), a city close to Liège, in Belgium, the region from which both the Meroving and Caroling families originate. He went to live in his father's villa in Jupille when he was around seven, which caused Jupille to be listed as possible place of birth in almost every history book. Other cities have been suggested, including, Prüm, Düren, or Aachen.

Life

Much of what is known of Charlemagne's life comes from his biographer, Einhard, who wrote a Vita Caroli Magni (or Vita Karoli Magni), the Life of Charlemagne.

Early life

Charlemagne was the eldest child of Pippin the Short (714 – 24 September 768, reigned from 751) and his wife Bertrada of Laon (720 – 12 July 783), daughter of Caribert of Laon and Bertrada of Cologne. The reliable records name only Carloman and Gisela as his younger siblings. Later accounts, however, indicate that Redburga, wife of King Egbert of Wessex, might have been his sister (or sister-in-law or niece), and the legendary material makes him Roland's maternal uncle through Lady Bertha.

Einhard says of the early life of Charles:

- It would be folly, I think, to write a word concerning Charles' birth and infancy, or even his boyhood, for nothing has ever been written on the subject, and there is no one alive now who can give information on it. Accordingly, I determined to pass that by as unknown, and to proceed at once to treat of his character, his deed, and such other facts of his life as are worth telling and setting forth, and shall first give an account of his deed at home and abroad, then of his character and pursuits, and lastly of his administration and death, omitting nothing worth knowing or necessary to know.

This article follows that general format.

On the death of Pippin, the kingdom of the Franks was divided—following tradition—between Charlemagne and Carloman. Charles took the outer parts of the kingdom, bordering on the sea, namely Neustria, western Aquitaine, and the northern parts of Austrasia, while Carloman retained the inner parts: southern Austrasia, Septimania, eastern Aquitaine, Burgundy, Provence, and Swabia, lands bordering on Italy. Perhaps Pippin regarded Charlemagne as the better warrior, but Carloman may have regarded himself as the more deserving son, being the son, not of a mayor of the palace, but of a king.

Joint rule

On 9 October, immediately after the funeral of their father, both the kings withdrew from Saint Denis to be proclaimed by their nobles and consecrated by the bishops, Charlemagne in Noyon and Carloman in Soissons.

The first event of the brothers' reign was the rising of the Aquitainians and Gascons, in 769, in that territory split between the two kings. Pippin had killed in war Waifer, Duke of Aquitaine. Now, one Hunald led the Aquitainians as far north as Angoulême. Charlemagne met Carloman, but Carloman refused to participate and returned to Burgundy. Charlemagne went to war, leading an army to Bordeaux, where he set up a camp at Fronsac. Hunold was forced to flee to the court of Duke Lupus II of Gascony. Lupus, fearing Charlemagne, turned Hunold over in exchange for peace. He was put in a monastery. Aquitaine was finally fully subdued by the Franks.

The brothers maintained lukewarm relations with the assistance of their mother Bertrada, but Charlemagne signed a treaty with Duke Tassilo III of Bavaria and married Gerperga, daughter of King Desiderius of the Lombards, in order to surround Carloman with his own allies. Though Pope Stephen III first opposed the marriage with the Lombard princess, he would have little to fear of a Frankish-Lombard alliance in a few months.

Charlemagne repudiated his wife and quickly married another, a 13-year-old Swabian named Hildegard. The repudiated Gerperga returned to her father's court at Pavia. The Lombard's wrath was now aroused and he would gladly have allied with Carloman to defeat Charles. But before war could break out, Carloman died on 5 December 771. Carloman's wife Gerberga (often confused by contemporary historians with Charlemagne's former wife, who probably shared her name) fled to Desiderius' court with her sons for protection. This action is usually considered either a sign of Charlemagne's enmity or Gerberga's confusion.

Charles and his children

During the first peace of any substantial length (780–782), Charles began to appoint his sons to positions of authority within the realm, in the tradition of the kings and mayors of the past. In 780, he had disinherited his eldest son, Pippin the Hunchback, because the young man had joined a rebellion against him. According to Charlemagne's biographer, Einhard, Pippin had been duped, through flattery, into joining a rebellion of nobles who pretended to despise Charles' treatment of Himiltrude, Pippin's mother, in 770. Charles renamed his son Carloman as Pippin to keep the name alive in the dynasty. In 781, he made his oldest three sons kings. The eldest, Charles, received the kingdom of Neustria, containing the regions of Anjou, Maine, and Touraine. The second eldest, Pippin, was made king of Italy, taking the Iron Crown which his father had first worn in 774. His third eldest son, Louis, became king of Aquitaine. He tried to make his sons a true Neustrian, Italian, and Aquitainian and he gave their regents some control of their subkingdoms, but real power was always in his hands, though he intended each to inherit their realm some day.

The sons fought many wars on behalf of their father when they came of age. Charles was mostly preoccupied with the Bretons, whose border he shared and who insurrected on at least two occasions and were easily put down, but he was also sent against the Saxons on multiple occasions. In 805 and 806, he was sent into the Böhmerwald (modern Bohemia) to deal with the Slavs living there (Czechs). He subjected them to Frankish authority and devastated the valley of the Elbe, forcing a tribute on them. Pippin had to hold the Avar and Beneventan borders, but also fought the Slavs to his north. He was uniquely poised to fight the Byzantine Empire when finally that conflict arose after Charlemagne's imperial coronation and a Venetian rebellion. Finally, Louis was in charge of the Spanish March and also went to southern Italy to fight the duke of Benevento on at least one occasion. He took Barcelona in a great siege in the year 797 (see below).

It is difficult to understand Charlemagne's attitude toward his daughters. None of them contracted a sacramental marriage. This may have been an attempt to control the number of potential alliances. Charlemagne certainly refused to believe the stories (mostly true) of their wild behaviour. After his death the surviving daughters entered or were forced to enter nunneries by their own brother, the pious Louis. At least one of them, Bertha, had a recognised relationship, if not a marriage, with Angilbert, a member of Charlemagne's court circle.

Death

"Europe at the death of Charles the Great, 814."—The Public Schools Historical Atlas ed. by C. Colbeck.

In 813, Charlemagne called Louis the Pious, king of Aquitaine, his only surviving legitimate son, to his court. There he crowned him as his heir and sent him back to Aquitaine. He then spent the autumn hunting before returning to Aachen on 1 November. In January, he fell ill. He took to his bed on 22 January and as Einhard tells it:

- He died January twenty-eighth, the seventh day from the time that he took to his bed, at nine o'clock in the morning, after partaking of the Holy Communion, in the seventy-second year of his age and the forty-seventh of his reign.

When Charlemagne died in 814, he was buried in his own Cathedral at Aachen. He was succeeded by his surviving son, Louis, who had been crowned the previous year. His empire lasted only another generation in its entirety; its division, according to custom, between Louis's own sons after their father's death laid the foundation for the modern states of France and Germany.

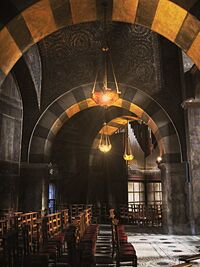

The imperial coronation of Charlemagne, an act of utmost importance in European history.

Notes

- ^ Pierre Riche, The Carolingians: A Family Who Forged Europe, University of Pennsylvania Press, 1993, ISBN 0-8122-1342-4

- ^ Oman, Charles. The Dark Ages 476–919. Rivingtons: London, 1914. Regards Charlemagne's grandsons as the first kings of France and Germany, which at the time comprised the whole of the Carolingian Empire save Italy.

Sources

- Einhard (1960) [1880]. The Life of Charlemagne. trans. Samuel Epes Turner. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press. ISBN 0-472-06035-X. http://www.fordham.edu/halsall/basis/einhard.html.

- Oman, Charles (1914). The Dark Ages, 476-918 (6th ed. ed.). London: Rivingtons.

- Painter, Sidney (1953). A History of the Middle Ages, 284-1500. New York: Knopf.

- Santosuosso, Antonio (2004). Barbarians, Marauders, and Infidels: The Ways of Medieval Warfare. Boulder, Colo.: Westview Press. ISBN 0-8133-9153-9.

- Scholz, Bernhard Walter; with Barbara Rogers (1970). Carolingian Chronicles: Royal Frankish Annals and Nithard's Histories. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press. ISBN 0-472-08790-8. Comprises the Annales regni Francorum and The History of the Sons of Louis the Pious.

Further reading

- Barbero, Alessandro (2004). Charlemagne: Father of a Continent. trans. Allan Cameron. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-23943-1.

- Becher, Matthias (2003). Charlemagne. trans. David S. Bachrach. New Haven: Yale University Press. ISBN 0-300-09796-4.

- Ganshof, F. L. (1971). The Carolingians and the Frankish Monarchy: Studies in Carolingian History. trans. Janet Sondheimer. Ithaca, N.Y.: Cornell University Press. ISBN 0-8014-0635-8.

- Langston, Aileen Lewers; and J. Orton Buck, Jr (eds.) (1974). Pedigrees of Some of the Emperor Charlemagne's Descendants. Baltimore: Genealogical Pub. Co..

- Pirenne, Henri (1939). Mohammed and Charlemagne. trans. Bernard Miall. New York: Norton.

- Sypeck, Jeff (2006). Becoming Charlemagne: Europe, Baghdad, and The Empires of A.D. 800. New York: Ecco/HarperCollins. ISBN 0-06-079706-1.

- Wilson, Derek (2005). Charlemagne: The Great Adventure. London: Hutchinson. ISBN 0-09-179461-7.

External links

- Charlemagne Chronology

- The Life of Charlemagne by Einhard. At Medieval Sourcebook.

- Vita Karoli Magni by Einhard. Latin text at The Latin Library.

- A reconstructed portrait of Charlemagne, based on historical sources, in a contemporary style.

- House of Pepin: Genealogy of Charlemagne.

- Charlemagne At Find A Grave

- Stoyan

- The Sword of Charlemagne (myArmoury.com article)

| This page uses content from the English language Wikipedia. The original content was at Charlemagne. The list of authors can be seen in the page history. As with this Familypedia wiki, the content of Wikipedia is available under the Creative Commons License. |